After watching a series of recorded talks and presentations, I have become a fan of Seth Godin. Like his talks, his blog is an explosion of ideas, and each idea is worth spending some time with and giving some serious thought. They are the type of ideas that even if they all turn out to be wrong, a person is still better off for having thought about them. The ideas are fresh. One idea that is stressed more than once is the importance of abandoning the idea of perfection, and shipping a product that is good enough.

At first, this didn’t sit very well with me. “Good enough” is a phrase I use very often. I am by no means a perfectionist with every detail in my life. The only area where I do strive for perfection is my art, because the arts are one area where I strongly believe that “good enough” is never good enough. Only the very best that I am capable of producing is ever good enough. This must be an area where business advice does not apply to the art world.

But this might be too literal of an interpretation on my part.

Godin’s real point, I think, is to raise the question, “is it better to never ship perfect, or always ship good enough?”

This idea fits in really well with one of Godin’s talks, where he was promoting his booklet, Ship-it. In the talk, Godin emphasizes that “good enough” doesn’t mean “bad” or “half-assed”. “Good enough” means that it is good enough for what people want/need/expect. In the case of art, the work itself might have to be perfect, but if it’s hung a few centimetres too high, and lowering the painting requires patching the hole from the first nail, and re-painting the gallery, and it’s 20 minutes to show time, then it’s OK to stop, shrug, and say, “good enough.”

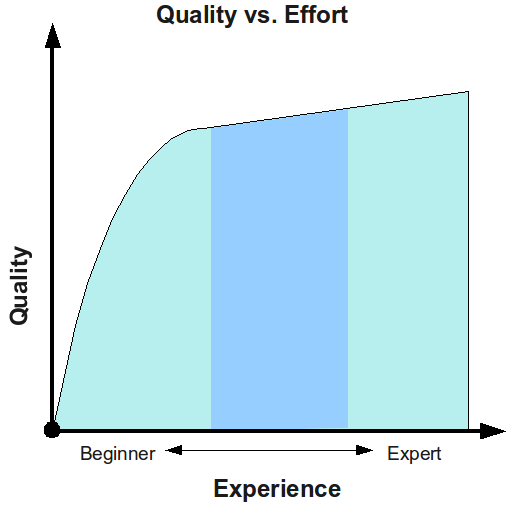

His chart, however, really struck a chord with me. It’s not exactly a scientific chart, but it is an image that explains the idea far better than words ever could. Rather than post a link to his chart, I have created my own version of it:

As a beginner, small amounts of practice lead to big gains in quality. As skill level improves, the payoff for each hour of practice becomes less and less. The same is true for effort or resources put into a project. Most of the really big gains are made in the early stages. By the end of development, large expenditures give imperceptible improvements. Eventually, a point is reached where further improvement just isn’t worth it.

I’m reminded of an old programmer’s joke: “The first 90% of the code accounts for the first 90% of the development time. The remaining 10% of the code accounts for the other 90% of the development time.” I’d be surprised if this joke is unfamiliar, since it has it’s own Wikipedia entry. The same rule in programming is equally true for art.

These past 3 weeks, I’ve been working on two paintings. I’ve known exactly how they were going to look when finished by the end of day 3. Reaching that point is 90% of the image-making process. The image is there in the under-painting, I just have to tweak it and make it look finished. The remaining 18 days have been spent trying to making the paintings look good. It’s hard to explain this in words, but I can look at a piece of art and say, “that looks amateur”, “that looks like student work”, and “that’s professional”. Getting my work to reach that level of professionalism that I demand from it takes a lot of time, even though it looks ‘almost done’ or ‘good enough’ throughout most of that period. It’s a little demotivating to pour hours into something, and when it is finally good enough to be declared ‘finished’, it looks no different from the initial under-painting in the documentation. All those little extras that take up 90% of the studio time are completely lost in the photos I take!

I think the gist of this idea is that an obsession with perfection in all things isn’t helpful. Sharp focus on key details, the details that really matter, that is what’s important.

The “Take a Picture” project is a perfect example of focusing only on what matters, and accepting “good enough” in other places. The part of that project that really matters is the secret image that appears on the back of your digital camera. It has to be clear, sharp, and refined. At first, this project looks like a piece of extreme minimalism. It looks very minimal, considering there is absolutely nothing on the canvas. Since the fist impression of this project is likely to evoke accusations of laziness on our part, we knew we would have to do something to counter this kind of reaction. We wanted the hidden image to look very crisp, flawless, and perfect, almost mechanical, so people would understand that a lot of skill, and a lot of work did go into this. If their first impression of us was followed with imagery that is rough and sloppy, it would reinforce that initial opinion; that’s not what we want.

What people see on the front is what matters. The electronics stuffed in the back aren’t nearly so important; they don’t have to be perfect. They just have to work. They have to be durable. They have to be hidden from view to not spoil the surprise. They have to run safely. Brads design does all those things. His design is extremely flexible, it’s parallel, so if one board were to fail, the rest of the chain will still work. The design allows for any number of additional circuits to be added to the chain, and each circuit can branch off into 3 separate chains, going in separate directions. But is it the absolute best circuit design possible? I don’t know; we didn’t spend a lot of time trying to invent new designs. Having the best possible solution or circuit doesn’t really matter in this case. Perfection doesn’t matter; functionality does.

Brad’s circuit design might not have been the fastest for us to manufacture. It may not be the most elegant to look at, or the cheapest to manufacture. This design was well tested; we know it works. And we had a bit of a stock pile left over from building the prototype, so re-using the design gave us a head start. Maybe we could have done something smaller, something simpler, something prettier on the back. We didn’t spend months of development, we didn’t consult world-leading electrical engineers, we didn’t tour numerous top-of-the-line manufacturing facilities. None of those things are important to this project. Fussing over these details would only have taken our attention away from the areas that do matter. We picked a design that we already had, one that we know for certain will work, and we know how to make it in large quantities. It does the job it has to do. It is good enough.